by Dixon Wragg

WaccoBB.net

“Subjective” and “objective” are basic concepts for understanding the world, and we are unclear on them at our peril.

The simple explanation is: “subjective” refers to whatever is going on inside our minds, including thoughts, feelings, perceptions, beliefs, dreams, interpretations and hallucinations, while “objective” refers to whatever exists independently of our minds, such as rocks, plants, animals, galaxies, solids, liquids, gasses, various forms of energy, other people, and even our own bodies.

Not all objective things are matter. Energy, e.g., light or microwaves, is objective and even physical, but it’s not matter. It can also be said that abstract things such as facts exist objectively. For instance, Pluto and the various facts about it (size, orbit, etc.) were real before anyone knew Pluto existed; thus these facts were objectively existent.1 Similarly, abstract principles such as differentiation and correlation existed before they were ever cognized by humans, so they’re in some sense objective, though not corporeal.

Many things are “intersubjective”, which means that, though they’re not objective (i.e., they have no existence outside of minds), they are available to many minds, not just one. For instance, religions, philosophies and other beliefs are intersubjective, shared by many, while your or my personal feelings and perceptions are more individually subjective. Here we must note that, no matter how many people believe something or how strongly they believe it, belief doesn’t make it true.

The subjective stuff is intangible. A rock or a leaf is a tangible, physical object, but it doesn’t physically enter our head when we see it or think of it, and thank goodness for that; we wouldn’t survive the experience! The leaf itself, if it’s a real leaf and not a hallucination or a fig leaf of our imagination (sorry), exists objectively, outside our minds. We cannot have the physical leaf in our minds; instead we have a proxy, a symbolic representation, such as an image or the idea of a leaf. The physical leaf that exists regardless of whether we ever encounter it is objective; our perception or thought of it is subjective.

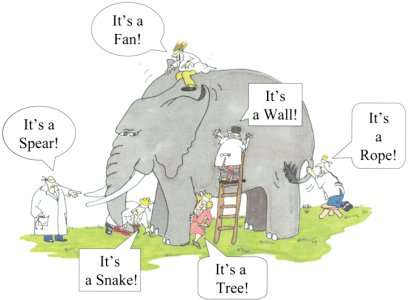

Note that this means we can never experience what Immanuel Kant called the “thing-in-itself” or “noumenon”; regarding objective things, we can experience only our sensory impressions of them, or “phenomena”2. There is an unavoidable degree to which we construct in our minds our every experience of the physical universe—the way it looks and feels to us. In other words, we can only perceive the objective universe through our subjective lenses. Our experience is always shaped by the structure, function and tuning of our sensory organs and brain, and by the brain’s programming.

For instance, different stars radiate in different wavelengths. Our local star, the Sun, radiates mostly in the range of the electromagnetic spectrum that has come to be called “visible light”. We evolved to see in that range precisely because that’s where most of the light is (in our solar system). If we orbited a star that produced more infrared or ultraviolet, we’d be seeing in that wavelength, and things would look different to us accordingly. Those who are “color-blind” see the same world differently, and those who are blind live in a nonvisual, more acoustic, tactile, olfactory and gustatory world. Thus different perspectives yield different valid views, yet it’s also possible to see things inaccurately, to be mistaken.

Additionally, the programming of our brain shapes our experience, sometimes quite fundamentally. For example, those who emphasize the oneness of all things will experience the same objects, people and events differently than those who feel alienated from, and competitive with, everyone and everything around them. These differences can be broadly cultural or individual.

None of this implies that the entire world is subjective, all in our heads. Seeing an objective world through our subjective filters is not the same as dreaming up a world from nothing. We reasonably infer, based on the continuity and verifiability of what we observe, that much of our experience is of things which exist objectively, not just in our heads3.

A big part of reasoning is figuring out just what is objectively real versus subjectively real. This brings us to a brief discussion of why the distinction is important:

Self-Centered Standards for Judgment Often people take their feelings (subjective) about something as a broadly applicable, objective standard for others’ behavior. For example, I seem to be incurably heterosexual. Whenever I’ve imagined having sex with a male, I’ve felt only disgust. But I don’t jump from this feeling to an assumption that homosexuality is wrong or harmful. As a critical thinker, I avoid such self-centered reasoning. But there are many who are only too quick to demonize, pathologize or criminalize others on the basis of their disgust or other feelings. The result: needless human suffering.

Objectifying the Subjective Another common fallacy involves taking a subjective feeling of certainty as evidence for some claim about the objective world. For instance, people commonly interpret their extremely strong and inspiring feeling that some god exists as evidence for its objective existence. Of course, such a strong feeling of certainty is usually only evidence that the person really, really wants the belief to be true.

Imagination, Perception and Suggestibility Another way of “objectifying the subjective” is to take our subjective experience for evidence of the objective reality of some apparent percept which is, in fact, all in our heads. During the “crystal power” fad of the 1980s, my friend Gretchen talked me into trying to feel a tingling sensation which she said would indicate some kind of energy emanating from a quartz crystal. She swept the crystal to and fro lengthwise over my hand. Feeling nothing, I closed my eyes to focus my concentration. Then I thought I noticed a very slight tingling, moving in the same direction she’d been moving the crystal! But opening my eyes revealed that she had changed direction; now the crystal was sweeping from side to side of my hand. I had imagined the tingling sensation going the direction I mistakenly thought the crystal was moving! Clearly, that tingling was all in my head (subjective), not caused by some objectively existent energy. So many people accept imaginary “evidence” for the existence of energies unknown to physicists or for the efficacy of various healing practices, interpreting changes in subjective symptoms such as pain, anxiety and depression as evidence of some objective physiological effect from the latest popular Sacred Snake Oil.

Subjectifying the Objective The other side of the “objectifying the subjective” coin is what I call (drum roll, please) “subjectifying the objective”. This is an evasive strategy used by some folks when confronted with factual evidence or compelling arguments they don’t want to hear. Instead of making an honest attempt to verify or disconfirm the unwelcome evidence, they simply say the magic words: “That’s just your opinion” or, more broadly, “That’s your truth, but everyone has their own truth”. Thus they reduce objective fact to the status of subjective supposition, neatly rendering themselves uncorrectable.

Objectivity More generally, we have the issue of being “objective” in our thinking. That means trying to correct for our subjective sources of distortion, such as feelings, biases and self-interest, so as to see things more clearly when assessing the truth of a claim. No one can be totally objective all the time, but it’s possible to be quite sufficiently objective in certain situations such as a scientific study, or addressing a particular issue. Objectivity is a remedy for egocentric and sociocentric thinking.

NOTES:

1. The apparently complicated relationship between human perception and certain characteristics of particles on the quantum level is outside the scope of this article, which focuses on more practical, human-scale concerns.

2. Kant, Immanuel Critique of Pure Reason

3. We’ll examine this issue a little more deeply in my next column.

-

Bulletin Board

Quick Nav

Bulletin Board

Quick Nav

- Bulletin Board

- Sonoma County Bulletin Board

- General Community

- The Gospel According to Dixon #3: Subjective/Objective

So Long and Thanks for All the Fish!

This site is now closed permanently to new posts.We recommend you use the new Townsy Cafe!

Click anywhere but the link to dismiss overlay!

- Share this thread on:

- Follow: No Email

-

Thread Tools

-

Search Thread

-

Dixon

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jul 19, 2005

-

Location: Santa Rosa

- Expressed Gratitude: 3,784

- Received Gratitude 1,839 times for 685 posts

-

Last Online 01-31-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,553)

View Posts: (1,553)

The Gospel According to Dixon #3: Subjective/Objective

Last edited by Dixon; 09-07-2011 at 06:44 AM. Reason: Rearranged my 5 main points near the end, and replaced their numbering with boldface headings to avoid confusion with footnote numbers

-

-

podfish

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Aug 5, 2006

- Expressed Gratitude: 1,150

- Received Gratitude 3,643 times for 1,544 posts

-

Last Online 02-07-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (2,239)

View Posts: (2,239)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

I've been spending a little time trying to understand what science has brought to the table regarding the nature of reality. For most of history, the major advances in understanding have come from those who were both philosophers and proto-scientists (I say proto because science in the modern sense of the word was developed only over the last few hundred years). There's been a strong effort to identify what exists independently of our observations. The math gets deep really quick and the analogies we fall back on quickly break down. One of the biggest hazards of using analogies is that they lead to excessive extrapolation. Just because two things are a little bit alike doesn't mean they're a lot alike....The simple explanation is: “subjective” refers to whatever is going on inside our minds, including thoughts, feelings, perceptions, beliefs, dreams, interpretations and hallucinations, while “objective” refers to whatever exists independently of our minds, such as rocks, plants, animals, galaxies, solids, liquids, gasses, various forms of energy, other people, and even our own bodies..

It seems that there really isn't any way to get around our perceptions. Some things just don't make sense; also, some things make sense even if they're provably wrong. It seems clear from the math that time is not an arrow, with the past leading to the future. But we live as if it is, and it "works" just fine for us that way. It doesn't work for us to try to treat the past the same way as the future. Here's where analogy and experience break down. It seems to follow that if time does not insist on going forward, we could travel back in time. But apparently that's not the case, and annoyingly the reasons for that are extremely subtle and difficult to understand.

A second example, one less 'magical' than time, is gravity. We all think we know about forces - we push things around all the time. Gravity sure seems like a force pulling us down. It works just fine if we treat it that way - we can even engineer vehicles based on that model of reality. But it's another thing that's proven to be untrue. That's what Einstein did to Newton - relativity theory apparently proves that Newton had misunderstood how reality works. Some of this stuff goes over my head pretty darn quickly, but if I understand it at all, it's debatable that there is anything but "events". As the name implies, relativity theory describes how the relative time and location of events can be used to describe the underlying reality. We perceive certain groups of events as individual objects; we perceive ourselves as objects that move linearly through time. Works great, pretty much all of us act as if it were true, but it seems to be an artifact of our bodies and minds rather than an accurate description of what's "real".

-

-

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

The way you've defined subjective and objective is problematic because the scope of objectivity is completely subsumed by the subjective. On the one hand, you say that means "whatever is going on in our heads" including, critically, perception. At the same time, "regarding objective things, we can experience only our sensory impressions of them".

By definition, then, objective phenomena are known only through subjective perception. and consequently there can be no objective proof of the objective world.

You're assuming the world is out there and we discover it--that the phenomena our senses show us are in fact true. There's no evidence for that belief.

-

Auntie WaccoSara S

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jan 13, 2007

-

Location: Sebastopol

- Expressed Gratitude: 10,042

- Received Gratitude 2,108 times for 906 posts

-

Last Online 07-12-2020

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (2,117)

View Posts: (2,117)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Dixon, this is brilliant; I never before knew how to answer people who told me "Well, that's your truth."

by Dixon Wragg

WaccoBB.net

“Subjective” and “objective” are basic concepts for understanding the world, and we are unclear on them at our peril.

The simple explanation is: “subjective” refers to whatever is going on inside our minds, including thoughts, feelings, perceptions, beliefs, dreams, interpretations and hallucinations, while “objective” refers to whatever exists independently of our minds, such as rocks, plants, animals, galaxies, solids, liquids, gasses, various forms of energy, other people, and even our own bodies.

...

-

-

podfish

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Aug 5, 2006

- Expressed Gratitude: 1,150

- Received Gratitude 3,643 times for 1,544 posts

-

Last Online 02-07-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (2,239)

View Posts: (2,239)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

"Your truth" is such a funny phrase, too. Kinda implies a Carolian view of words: 'they mean what I say they do'. You can certainly go deeper into its meaning, but generally the word implies existence of a single reality, or at least a singular aspect of reality.

There's an immense amount of writing about ideas like "truth" by a lot of very thoughtful people. So many people ignore that part of our heritage and have way too much respect for their own half-assed interpretations based on their own feelings and experience. I won't exempt myself.... but I encourage all of us to make the effort to build our own ideas on the wisdom of our predecessors.

-

-

Dixon

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jul 19, 2005

-

Location: Santa Rosa

- Expressed Gratitude: 3,784

- Received Gratitude 1,839 times for 685 posts

-

Last Online 01-31-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,553)

View Posts: (1,553)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Thanks, Sara! My next column, entitled "Reality Is Real--Really!", will go into that issue more deeply, so don't miss it. I think it's due to be published by the end of this month.

-

-

Dixon

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jul 19, 2005

-

Location: Santa Rosa

- Expressed Gratitude: 3,784

- Received Gratitude 1,839 times for 685 posts

-

Last Online 01-31-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,553)

View Posts: (1,553)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Thanks for your cogent comments, podster.

Podster, this reminds me of what an 18th-century wit said about Berkeley's philosophical attempts to do away with matter, and Hume's to do the same with mind: "No matter, never mind."...if I understand it at all, it's debatable that there is anything but "events"...We perceive certain groups of events as individual objects; we perceive ourselves as objects that move linearly through time. Works great, pretty much all of us act as if it were true, but it seems to be an artifact of our bodies and minds rather than an accurate description of what's "real".

It seems to me the term "events" implies the existence of things (a term which includes people) which are doing something; thus time and probably also space are implied. You may mean something a little different by the term "events". If I were to posit the non-existence of objective reality, I'd probably refer to something like "perceptions", "ideas", "images", but I think even those ultimately imply some objective reality--at least a brain.

-

-

podfish

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Aug 5, 2006

- Expressed Gratitude: 1,150

- Received Gratitude 3,643 times for 1,544 posts

-

Last Online 02-07-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (2,239)

View Posts: (2,239)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

the original quote of mine was "We perceive certain groups of events as individual objects" which is what I drew from Bertrand Russell's explanations. This is physics, not metaphysics, if there's a difference at that level.

My read was that 'events' are the ineffable center of it all - in the literal sense of the adjective since I can't imagine a way to pin them down with any sort of description. It's the groupings and relationships of events that create reality for us - some groups get perceived as objects that persist through time (which itself is revealed as a relationship between events or groups of events). My guess is that they're not particularly useful in metaphysics, but a necessary part of the mathematics of relativity. It's fairly common for the terms in an equation to be paired with familiar concepts. Often that leads to misunderstanding of what the equations actually mean.

-

-

Auntie WaccoSara S

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jan 13, 2007

-

Location: Sebastopol

- Expressed Gratitude: 10,042

- Received Gratitude 2,108 times for 906 posts

-

Last Online 07-12-2020

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (2,117)

View Posts: (2,117)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Hey, Dixon: This reminded me of a somewhat tweaked version of Hume from back in the '80s:

If you don't mind, it doesn't matter.

Thanks for your cogent comments, podster.

Podster, this reminds me of what an 18th-century wit said about Berkeley's philosophical attempts to do away with matter, and Hume's to do the same with mind: "No matter, never mind."

It seems to me the term "events" implies the existence of things (a term which includes people) which are doing something; thus time and probably also space are implied. You may mean something a little different by the term "events". If I were to posit the non-existence of objective reality, I'd probably refer to something like "perceptions", "ideas", "images", but I think even those ultimately imply some objective reality--at least a brain.

-

-

Dixon

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jul 19, 2005

-

Location: Santa Rosa

- Expressed Gratitude: 3,784

- Received Gratitude 1,839 times for 685 posts

-

Last Online 01-31-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,553)

View Posts: (1,553)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Oooops! I initially included in this response references to my 4th column, which hasn't quite been published yet, confusing it with my 3rd column ("Subjective/Objective"). Sorry for any confusion, Sean and everybody! I'll go through this post and edit it for clarity now:

Yes, but can we agree, Sean, that there is something fundamentally different between, for instance, a dream about a rock, a picture of a rock, a hallucination of a rock, the concept of "rock", and an (apparently) physical rock that we've just painfully stubbed our toe on?The way you've defined subjective and objective is problematic because the scope of objectivity is completely subsumed by the subjective. On the one hand, you say that means "whatever is going on in our heads" including, critically, perception. At the same time, "regarding objective things, we can experience only our sensory impressions of them".

OK, "...no objective proof of the objective world" [emphasis mine], but that's not the same as saying "no proof of the objective world" (keeping in mind that we can never prove anything for sure, 'cause we could always be mistaken). By definition, then, objective phenomena are known only through subjective perception. and consequently there can be no objective proof of the objective world.

By definition, then, objective phenomena are known only through subjective perception. and consequently there can be no objective proof of the objective world.

No, it's not an assumption; it's a near-certain conclusion based on reasoning from observations. You're assuming the world is out there and we discover it...

You're assuming the world is out there and we discover it...

Clarification: I'm saying that some of "the phenomena our senses show us" correspond to objectively real referents (i.e., the real rock I stubbed my toe on), some is just subjective reality (thoughts, dreams, etc.), and some is subjective experience mistaken for objective reality (misperceptions, hallucinations, fallacious conclusions, etc.). --that the phenomena our senses show us are in fact true.

--that the phenomena our senses show us are in fact true.

On the contrary, keeping in mind that nothing can be proven to absolute certainty, I'll be mentioning what I think are several good arguments for objective reality in my next column, which should see publication any day now under the title "Reality Is Real--Really!". I'll just briefly mention a couple of the arguments now, such as the necessity for a physical brain supported by a physical ecosystem, supported by a physical substrate (the planet) in order for our subjective experience to even exist. Also, consider that you and I have both stubbed our toes on rocks we didn't see first (thus our pain wasn't an expectation effect involving a hallucinated rock), and that I can leave an object someplace and you can come along and find it (thus continuity and verifiability). There are other good arguments, too. Again, keeping in mind that absolute certainty either way is chimerical, the question is: What is most likely, that there is an objective universe or that there isn't--that it's all in Sean's head and the rest of us are figments of his imagination? We've got bad news for you Sean--you're gonna have to readjust your assessment of your centrality in the universe. Most of us objects in your perceptual field are independently existent--not just props in your subjective play. There's no evidence for that belief.

There's no evidence for that belief.

If you still insist that nothing's objectively real, please give me your house, car and girlfriend; you can imagine yourself some new ones.Last edited by Barry; 05-04-2011 at 05:49 PM.

-

-

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Dixon, I haven't asserted anything--you have. I'm exploring your definitions, whether they are sound, and what they imply. Please don't conclude that you know what I might believe merely because I question the logic behind your statements and definitions.

It's an interesting question, perhaps it's more useful to think of it this way: let's say you dream that you painfully stub your dream-toe on a dream rock. You experience dream-pain. Then you stub your awake toe on an awake rock and experience awake pain. Are the two pains different? How do you know?Yes, but can we agree, Sean, that there is something fundamentally different between, for instance, a dream about a rock, a picture of a rock, a hallucination of a rock, the concept of "rock", and an (apparently) physical rock that we've just painfully stubbed our toe on?

I don't understand, from your definitions or your discussion, what you mean by "objectively real referents". There's ambiguity because, according to you, the objectively real is apprehended by way of the subjectively unreal. I suspect that, by objective, you mean some kind of experience that has its qualities independent of any observation. Posted in reply to the post by dixon:

Clarification: I'm saying that some of "the phenomena our senses show us" correspond to objectively real referents (i.e., the real rock I stubbed my toe on), some is just subjective reality (thoughts, dreams, etc.), and some is subjective experience mistaken for objective reality (misperceptions, hallucinations, fallacious conclusions, etc.).

Posted in reply to the post by dixon:

Clarification: I'm saying that some of "the phenomena our senses show us" correspond to objectively real referents (i.e., the real rock I stubbed my toe on), some is just subjective reality (thoughts, dreams, etc.), and some is subjective experience mistaken for objective reality (misperceptions, hallucinations, fallacious conclusions, etc.).

Perhaps we could look at something like the "blueness" of the sky or the redness of a rose to understand, by way of example, what is objective about that sky's blue or that rose's red and what isn't.

-

Dixon

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jul 19, 2005

-

Location: Santa Rosa

- Expressed Gratitude: 3,784

- Received Gratitude 1,839 times for 685 posts

-

Last Online 01-31-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,553)

View Posts: (1,553)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

On the contrary, Sean, a quick perusal of your previous post will show several declarative sentences (assertions) from you. The one I'm finding most interesting to explore is this one: "There's no evidence for that belief" [that "the world is out there and we discover it", i.e., that there's an objective universe independent of our subjective experience.]

Sean, I acknowledge that your absolutistic statement that "There's no evidence for that belief" (while a much stronger assertion than saying you haven't seen any compelling evidence for the claim) is not the same as saying the belief isn't true, and that I sounded as if you'd said the latter. Sorry about that! I'm exploring your definitions, whether they are sound, and what they imply. Please don't conclude that you know what I might believe merely because I question the logic behind your statements and definitions.

I'm exploring your definitions, whether they are sound, and what they imply. Please don't conclude that you know what I might believe merely because I question the logic behind your statements and definitions.

Having said that, let me also say that if I thought there were no evidence for a particular belief, I would reject the belief as untrue, if for no other reason than the fact that claims lacking evidence are much more likely to be false than true. That seems the most reasonable response to a situation in which no evidence for a claim is recognized. At this point, these questions are obvious: Even though you think there's no evidence for it, do you 1. Believe that the universe is at least partly objective? 2. Believe that there's no objective reality whatsoever--that "Life is but a dream"? 3. Choose agnosticism on this issue? or 4. Something else?

Good question. If we focus on a specific percept, such as toe pain, that very specific experience may seem the same regardless of whether it's in a dream or in waking life. But the context is always different. In the dream, it's only a matter of time before abrupt changes take place in ways that are fundamentally different than in waking life, which has more of a continuity. So, for instance, in a dream you may stub your toe on a rock, then find yourself in a room devoid of rocks with no experience of having traveled there, then find yourself with a beard you didn't have a minute earlier, then start flying by flapping your arms, then wake up to discover an unstubbed toe! This kind of stuff doesn't happen in real life, which has a more consistent continuity characterized by limitations such as gravity and consequences (so that your toe may hurt for days if you've stubbed it badly enough). Focusing myopically on single events like toe-stubbing without looking at context is not a good way of comparing dream reality with waking reality. ...let's say you dream that you painfully stub your dream-toe on a dream rock. You experience dream-pain. Then you stub your awake toe on an awake rock and experience awake pain. Are the two pains different? How do you know?

...let's say you dream that you painfully stub your dream-toe on a dream rock. You experience dream-pain. Then you stub your awake toe on an awake rock and experience awake pain. Are the two pains different? How do you know?

Nope. The term "objective" refers to things (physical objects, substances, principles, facts) that exist independently of anyone's subjective experience, not to experience, which is by definition subjective. We perforce experience all these things through our subjective "lenses", so that some of the qualities we may attribute to them (such as beauty, for instance) are subjective, but other qualities (such as size, or duration in time) are objective. We cannot experience them objectively (except in a relative sense), but we infer that there are often objects behind the phenomena we perceive because that's the most reasonable interpretation of our experience. I don't understand, from your definitions or your discussion, what you mean by "objectively real referents". There's ambiguity because, according to you, the objectively real is apprehended by way of the subjectively unreal. I suspect that, by objective, you mean some kind of experience that has its qualities independent of any observation.

I don't understand, from your definitions or your discussion, what you mean by "objectively real referents". There's ambiguity because, according to you, the objectively real is apprehended by way of the subjectively unreal. I suspect that, by objective, you mean some kind of experience that has its qualities independent of any observation.

Good examples. The blueness of the sky we experience is a confluence of objective and subjective factors. The objective factors include the chemical composition of the atmosphere, the behavior of light when it is scattered by atmospheric compounds, the wavelengths of the light thusly scattered, and the physical structure, function and tuning of our eyes and visual cortices. The subjective aspect is the experience of sky-blueness, which is a little painting in our minds triggered and shaped by those objective factors, and the associated feelings. Change some of the objective factors, such as the wavelength of the light being observed, and you get the subjective experience of rose-redness instead, with its associated feelings. Perhaps we could look at something like the "blueness" of the sky or the redness of a rose to understand, by way of example, what is objective about that sky's blue or that rose's red and what isn't.

Perhaps we could look at something like the "blueness" of the sky or the redness of a rose to understand, by way of example, what is objective about that sky's blue or that rose's red and what isn't.

There's a lot more I could say about this, but I'm getting ahead of myself, because I try to make a more thorough case for the existence of the objective universe and against the "Life is but a dream" model in my next column, which will be published as soon as Barry can find some time to help me iron out a little problem with the photos I want to include. So hopefully you'll find that column more satisfying.

Thanks for sharing your thinking, Sean!Last edited by Dixon; 05-06-2011 at 02:00 AM. Reason: a few tweaks for clarity, etc.

-

-

Supporting memberneil

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jan 7, 2008

- Expressed Gratitude: 98

- Received Gratitude 121 times for 34 posts

-

Last Online 12-09-2020

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (65)

View Posts: (65)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Hi Dixon,

This discussion interests me greatly, but I've been too busy (and other things) to get actively involved.

On another WaccoBB topic, Mad Miles quotes himself as saying: "It is hard to be really, really angry, and really, really sad, at the same time." Seems some "reality" is at work here, that this would be so.

Also, years ago I learned that if I am angry or just feeling down, if I skip with all my might, it brings an immediate big positive shift in how I feel. (You can try it yourself.) Doesn't this suggest that "subjective" feelings do indeed have definite "reality" connection? I mean, feeling isn't autistic.

We can "sense" the space behind our backs, quite apart from the five senses. We can also "feel" when we are being watched, and so (I observe) can other animals.

The same body that perceives it's living-in-the-world also feels it. It's not two bodies.

Thanks for stimulating thinking.

-

-

Dixon

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jul 19, 2005

-

Location: Santa Rosa

- Expressed Gratitude: 3,784

- Received Gratitude 1,839 times for 685 posts

-

Last Online 01-31-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,553)

View Posts: (1,553)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Well I'm honored that you've found the time to join in, Neil!

An interesting practice. Reminds me a bit of laughter yoga. I will indeed try it out. Also, years ago I learned that if I am angry or just feeling down, if I skip with all my might, it brings an immediate big positive shift in how I feel. (You can try it yourself.)

Also, years ago I learned that if I am angry or just feeling down, if I skip with all my might, it brings an immediate big positive shift in how I feel. (You can try it yourself.)

I'm not sure what you mean by the "autistic" comment, Neil, but I certainly haven't suggested that subjective reality isn't real. I've just taken pains to distinguish it from the objective type of reality, and to explicate some of the reasons why it's important that we not confuse the two. Doesn't this suggest that "subjective" feelings do indeed have definite "reality" connection? I mean, feeling isn't autistic.

Doesn't this suggest that "subjective" feelings do indeed have definite "reality" connection? I mean, feeling isn't autistic.

It's not clear to me that either of these things is true, Neil, though I'm entirely open to having them proved. I am pretty clear on the fact that our "unsystematic" (i.e., non-scientific, day-to-day) judgments on such things are not very trustworthy. For instance, let's say I gaze at someone (person or animal) from behind and they turn around and look at me, and this happens repeatedly. How do I know there weren't other reasons for them to turn around, having nothing to do with their sensing my gaze? Controlling those various confounding factors is what science is all about, and that's why well-designed, independently replicated studies would be necessary to convince me of these effects you describe. Perhaps such research already exists and I just haven't seen it yet...? I'm open to looking at it if you know of some. We can "sense" the space behind our backs, quite apart from the five senses. We can also "feel" when we are being watched, and so (I observe) can other animals.

We can "sense" the space behind our backs, quite apart from the five senses. We can also "feel" when we are being watched, and so (I observe) can other animals.

Sorry, but I don't understand what you're saying. For instance, I don't get the distinction you're making between "perceiving" and "feeling" here. The same body that perceives it's living-in-the-world also feels it. It's not two bodies.

The same body that perceives it's living-in-the-world also feels it. It's not two bodies.

And thank you for the same, Neil! Thanks for stimulating thinking.

Thanks for stimulating thinking.

-

-

"Mad" Miles

"Mad" Miles

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jun 8, 2005

-

Location: Forestville, California, United States

- Expressed Gratitude: 1,263

- Received Gratitude 742 times for 362 posts

-

Last Online 11-05-2012

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,567)

View Posts: (1,567)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Just want to point out that these are very old questions being discussed here. Descartes, Berkeley, Locke and Hume were here long before you guys got into talking about perception vs. reality. Or objective vs. Subjective. Or the knowable vs. the speculative. Or plus vs. negative. (Beware the binary oppositional. Is it a habit of the mind? Or the very framework in which we are trapped by the nature of the way our minds work?)

Good holding down the fort Dixon. In a recent discussion you seemed to be conflating belief as: a fixed idea, held in the face of all contradictory evidence, argument or doubt, i.e. "Faith", with knowing something is going to happen. As in, "I 'believe' the sun will rise in the morning, because my own experience, and every reported account before me from the experience of others (others being sentient human beings, note the qualification "sentient" :-D) says it is pretty much guaranteed to happen, although we entertain the remote possibility that we're all totally bonkers!".

Absolute Faith is not the same thing as qualified confidence in fairly established and predictable outcomes, sometimes also referred to as "belief". Many a freshman dorm argument has been sustained by this confusion. Not to mention bloody, destructive wars. And every human folly about ideas, or at least a whole lot of them, in between.

OK, please continue...

But read up! Talkin' shit without knowing where shit comes from? You figure it out. But learn some shit!! Cause if you don't, then you don't know... What? What he talk'in 'bout???

It's late, I have more mundane concerns. As a philosophy student who studied the Canon (West and East and South and North and all the way through and back and around again and why do spacial metaphors mean anything, what are we? Trapped?? MF's?!) back in the day, this is actually a pretty pedestrian discussion. But I'm all about popular education.

And Everything I've just written applies to me as much as anyone else. So, Step Off!

Like I said, it's late.

-

-

Dixon

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jul 19, 2005

-

Location: Santa Rosa

- Expressed Gratitude: 3,784

- Received Gratitude 1,839 times for 685 posts

-

Last Online 01-31-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,553)

View Posts: (1,553)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Yo, Miles--

Of course, but my intended audience for this series is the average Joe or Jane for whom much of this will be new.

As I've mentioned before, Miles, I consider the polaristic account of the relationship between opposites, AKA the Yin-Yang principle, to be the best description of the workings of both human consciousness and reality itself. ...perception vs. reality. Or objective vs. Subjective. Or the knowable vs. the speculative. Or plus vs. negative. (Beware the binary oppositional. Is it a habit of the mind? Or the very framework in which we are trapped by the nature of the way our minds work?)

...perception vs. reality. Or objective vs. Subjective. Or the knowable vs. the speculative. Or plus vs. negative. (Beware the binary oppositional. Is it a habit of the mind? Or the very framework in which we are trapped by the nature of the way our minds work?)

I'll be writing a column on that in a few months, so stay tuned.

I'll be writing a column on that in a few months, so stay tuned.

Miles, I certainly didn't purposely conflate closed-minded blind faith with the more reasonable type based on proper reasoning from empirical observation. If you think I did so, please point out the quote(s) from me, and I'll consider re-wording for clarity. In any case, I'll be devoting at least part of an upcoming column to the different types of "faith". ...In a recent discussion you seemed to be conflating belief as: a fixed idea, held in the face of all contradictory evidence, argument or doubt, i.e. "Faith", with knowing something is going to happen. As in, "I 'believe' the sun will rise in the morning...etc. etc.

...In a recent discussion you seemed to be conflating belief as: a fixed idea, held in the face of all contradictory evidence, argument or doubt, i.e. "Faith", with knowing something is going to happen. As in, "I 'believe' the sun will rise in the morning...etc. etc.

Yeah, what are you talkin' 'bout? Are you suggesting that I read something in particular? Or absorb a doctorate's worth of philosophy studies just so I can write this column from a more well-read perspective? It ain't gonna happen, Miles. I'm always behind on my reading, and the last thing I want to do is add to my reading list a pile of pseudo-intellectual sophistry from a bunch of self-important philosoraptors. In order to even start this column, I had to overcome my perfectionism and decide that I have something to contribute without having to read more and more and more (without ever being satisfied). So if there's something in particular you think I'm missing, please lay it on me yourself without making me read all that crapola! But read up! Talkin' shit without knowing where shit comes from? You figure it out. But learn some shit!! Cause if you don't, then you don't know... What? What he talk'in 'bout???

But read up! Talkin' shit without knowing where shit comes from? You figure it out. But learn some shit!! Cause if you don't, then you don't know... What? What he talk'in 'bout???

Poor thing! I do sympathize. ...As a philosophy student who studied the Canon (West and East and South and North and all the way through and back and around again...) back in the day...

...As a philosophy student who studied the Canon (West and East and South and North and all the way through and back and around again...) back in the day...

And that's what this column is about, too--practical, useful info on, mainly, Critical Thinking, aimed at those who might be able to benefit from it, or at least enjoy the discussion. After all, Miles, we can't all operate on your ethereal level! ...this is actually a pretty pedestrian discussion. But I'm all about popular education.

...this is actually a pretty pedestrian discussion. But I'm all about popular education.

-

-

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

I don't have your education or learning so if you can correct our mistakes, that will be helpful. But driving by to tell us that our discussion is commonplace isn't very useful.Just want to point out that these are very old questions being discussed here...

It's late, I have more mundane concerns....

As a philosophy student who studied the Canon ... this is actually a pretty pedestrian discussion....

But I'm all about popular education.

-

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

I think it's an incorrectly stated question, for our discussion. It assumes that there are two ontological states to which our experience can belong--objective or subjective (or an admixture, I suppose). To make this assumption, we have to abstract conciousness away from experience--and I don't think that's meaningful.At this point, these questions are obvious: Even though you think there's no evidence for it, do you 1. Believe that the universe is at least partly objective? 2. Believe that there's no objective reality whatsoever--that "Life is but a dream"? 3. Choose agnosticism on this issue? or 4. Something else?

I may be wrong, but it seems to me that you're looking at the world as if there are truly existing objects "out there", and the qualities or attributes of those objects are attached to them. Like the blueness of the sky: the sky really exists out there, and its blueness is a kind of emergent property that occurs in the interface between the objectively existing sky's physical properties and the subjective viewer.

But there are a number of problems with this approach, I think. Any whole entity--the sky, a table, a tree--is necessarily composed of attributes--its parts. But none of the parts are the whole object. As you point out, the blueness of the sky depends on photons, the chemical composition of the sky, the properties of refraction, atmospheric pressure--and an observer with the right physical apparatus. No single one of these elements is the sky, they are merely attributes of an object called "sky". And each of these attributes occur in other objects--the chemicals in the sky are found elsewhere, photons are elsewhere, other objects have refraction.

This relationship of a whole to its parts is generally applicable to every apprehended phenomena. Now, giving any kind of primacy to the whole over its parts is nonsensical. Ontologically, it would be saying something like: there has to be an object there for the all the parts to be attached to, and that object has to come "first". It has to be there. But that's not a given; there's no a priori reason that should be the case. Epistemologically, it's saying: we need the whole first in order to have parts. But that's also nonsensical because there's no whole object independent of its constituent elements.

It may be easier to think through it with a manufactured object. For example, it's like saying: there's a knowable object called "table", which owns its various parts like the legs, the tabletop, etc. And this table is different that its parts--the table is owner of the parts. Of course that has all sorts of logical difficulties--theoretically, the table could be in one room and all its parts could be in another. Or the table is the sum of the parts, configured in a certain way. But then if I take one piece away, then it's no longer a table. It's actually rather hard to speak about the parts of a specific table without having the table as a concept. And it's hard to speak about a specific table that has no parts. So to say that the whole table comes first or the parts come first (as independently existing objects or real attributes) is to assign primacy where none exists

So the notion of an "object" that has some intrinsic existence is fraught with issues. And that's why asking questions about the mode of existence of that "object" might not be the best approach. The question itself is problematic.

-

podfish

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Aug 5, 2006

- Expressed Gratitude: 1,150

- Received Gratitude 3,643 times for 1,544 posts

-

Last Online 02-07-2021

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (2,239)

View Posts: (2,239)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

I don't know, there seem to be a lot of people who don't stop to consider that there's usually a lot of pre-existing context that can be brought to a discussion. A little reminder doesn't seem out of place to me.

-

-

"Mad" Miles

"Mad" Miles

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jun 8, 2005

-

Location: Forestville, California, United States

- Expressed Gratitude: 1,263

- Received Gratitude 742 times for 362 posts

-

Last Online 11-05-2012

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,567)

View Posts: (1,567)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Dixon,

My comment about "Read up!" was not directed at you personally. Sometimes when writing I shift voice and audience without telegraphing the move. A close reading and looking at the context and subject of each paragraph had clues as to when I do that. I'm not writing academese here. I'm not making a closely argued statement. I'm riffing.

The specific language where you were talking about, belief as fixed faith at one point, and as mere practical conviction at another, is further up?, down? the thread? Except that I don't see it below. I have a fairly distinct memory of it. Perhaps it is on another thread devolved from your articles about what constitutes reason and reality.

Instead of taking it as a specific critique of something you wrote (I don't have the time and inclination to dig up what prompted me to have that criticism) I'll now say, to everyone reading this, that it's my account of an error that I often see repeated in discussions such as these.

Belief, like True, Wrong, False, Justice, Freedom, Good, Bad, etc. is a Floating Signifier, the meaning of which can change, subtly or totally, depending on the context in which it is used. Much human nastiness has come down the pike when people insist that the "Big Ideas" are exactly what they are, no deviation in meaning or importance, and "we" control the definitions, or access them in the unchanging Sphere of the Absolute, and anyone who doesn't accept that, either must be made to, or deserves to die.

There has been progress in the course of human history, in the way we think about basic matters of reason, truth, perception vs. reality, etc. That's why I refer people to the canon. Many of these conundrums have been thoroughly discussed before, so if one is truly interested in the various takes on these issues, it would behoove "you" (you being anyone interested in the subject) to "read up".

I'm not saying go get a B.A. M.A. and then Ph.D. in Philosophy. But there are good histories and encyclopedia of philosophy available. Written for a popular audience.

I see a lot of ideas tossed around here that mix and match different schools and different periods and debates in the history of philosophy. Few if any references to where those ideas came from. These subjects are complex enough by themselves. Without some sense of the lay of the land, the history of human thinking, at least a general one, I sometimes see people talking past each other because the origins of their ideas are not acknowledged, or perhaps not even known to them.

Philosophers are taught to write clearly (believe it or not!) and to unpack their thinking so all of their steps are clear to anyone educated in the history, both of and between, competing schools and movements. If someone with the world view of a German Romantic dialectician, is arguing with someone with the world view of an English Empiricist rationalist, well not much is going to come out of that conversation. Unless they've both studied the others' school, their conceptual framework, and then something new may arise. (Any guesses as to which Philosophers I'm generally hinting at?)

In these discussion, on this and related Waccobb threads, I see some confusion which arises, similar to the confusion I referred to in previous paragraphs.

And by the way, even if you were merely jesting, I do not see myself as elevated, angelic, celestial, or in any other way "superior" to anyone else. But I have been interested in the play of ideas that we naked apes have come up with in our time on the planet. So, maybe, I've read some of the books with those ideas in them. Some, being the modal term in the previous sentence. By 1987, when it became clear to me I wasn't going to have, or choose, a career as an academic, I quit reading theory and returned to my original literary love, various kinds of modern fiction.

Everybody knows we're all making it up as we go, right? But by "making it up" I don't mean, whatever anyone thinks/believes is true, or that we only have our "own" truths. What we "make it up" with, and what it is we make up, are comprised of many things, including the ideas, perceptual apparati, conceptual frameworks, social, cultural and family conditioning, experience and education, that we inherited, absorbed and translated from others, going far back into the past.

Another key distinction is that scientific, mathematical, "objective" truth and reason, are not the same as truth and reason related to subjective matters, The Social, economics, sociology, history, philosophy. I'm not making a hard and fast distinction here. There is a lot of slippage and overlap between all of these realms of knowledge. There is objective historical truth, facts which are not in dispute. Same goes for all of the Humanities and "Soft" Sciences. And let's not forget The Arts!

But whether truths about the material world, are the same or different from the social world, and what the relationship and differences are? Well, whole schools of philosophy are based on different takes about all that. Not to mention the historical "progress" made on those questions, within a culture. Or rather to mention and highlight that fact that we are nodes in a river of time and influence, not monads without connection to each other and our collective past.

So, Read Up!

Everyone, myself included.

Anyway, gotta go. I live on Facebook these days.

-

-

"Mad" Miles

"Mad" Miles

-

Real Name: (not displayed to guest users)

-

Join Date: Jun 8, 2005

-

Location: Forestville, California, United States

- Expressed Gratitude: 1,263

- Received Gratitude 742 times for 362 posts

-

Last Online 11-05-2012

- View Profile

-

Ignore

Ignore

-

View Posts: (1,567)

View Posts: (1,567)

Re: The Gospel According to Dixon: Subjective/Objective

Sean,

As I wrote in my partly tongue in cheek comment that apparently irritated you, ("drive by") ...And Everything I've just written applies to me as much as anyone else. So, Step Off!

If you don't like being told that the level of discussion is on par with a late night dorm bull session, that's fine. I'm not seeking agreement. We are talking about philosophy, right? Have you ever attended an academic philosophy seminar? Agreement ain't what it's about.

As for "drive by"? Cracker? Please!!!??? At least give me credit for a Drive Through!! Leaving smashed bodies in my powerful wake! Oh, Wait, that wasn't my intent either...

If you don't like my tone or the content of my "contributions", ignore me. I've found that to be the best policy, for myself at least, here in Waccolandia. It's not like we're getting graded on our results here. Are we?

And "pedestrian", isn't that the mode of transport most often advocated here by the alternative energy crunchie crowd? What's wrong with that? In this social context, I would think it would be considered a COMPLIMENT! Maybe I should have written, "This bicycling discussion...." ;-D

Jeeze, everyone's so thin-skinned these days. Must be something in the air...

-

Gratitude expressed by 5 members:

Gratitude expressed by:

Gratitude expressed by:

Gratitude expressed by 4 members:

Gratitude expressed by:

Gratitude expressed by 2 members:

Gratitude expressed by 2 members:

Gratitude expressed by:

Gratitude expressed by:

Gratitude expressed by:

Gratitude expressed by:

- Site Areas

- Settings

- Private Messages

- Subscriptions

- Who's Online

- Search Categories

- Categories Home

- Categories

- Sonoma County Bulletin Board

- General Community

- Coronavirus

- Coronavirus Conspiracy Theories

- Events, Classes and Meetings

- Business Directory

- Sales & Timely Offers

- Services/Referrals Wanted

- Health & Wellness

- For Sale/Free/Wanted

- Employment Offered & Wanted

- Housing/Offices

- WaccoElders

- Housesitting/Petsitting

- Pets and other Critters

- Marin County Bulletin Board

- Discussion Board

- About WaccoBB

Similar Threads

-

Article: The Gospel According to Dixon #1: Let's Be Reasonable

By Dixon in forum General CommunityReplies: 33Last Post: 05-05-2011, 08:06 AM -

Article: The Gospel According to Dixon #2: Enlightenment

By Dixon in forum General CommunityReplies: 6Last Post: 02-16-2011, 11:12 PM -

Thanks, Dixon!

By Moon in forum General CommunityReplies: 0Last Post: 06-13-2006, 06:22 PM

Bookmarks

-

Facebook

Facebook

-

Twitter

Twitter

-

StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon